VOICES OF DAVIDSON

Colored Water

But the person he loved most in the world, besides Angeline and before he met my mother, was a woman named Alice, who was married to a man named Sam. Alice and Sam Allen came into my father’s life when daddy was a small boy and his brother, Dudley, was only a few years older. They lived together in a big house in Beaumont, while my grandfather ran the family lumber business and while Sam and Alice kept close care of the Oldham clan. Daddy thought of Alice as his other mother. Alice cooked all his favorite things and made sure that he didn’t get in too much trouble with Mr. Gus, hiding his peccadilloes and wrapping her voluminous apron around him to protect him from the hickory switch.

When the depression finally reached east Texas, the Oldham family lost everything, except one shack on one lumber yard. The other yards and thousands of acres were all gone. When Gus loaded up the family car to move the family to the shack, he turned to my daddy, who was about thirteen years old at the time, and asked if he had any money for gas. That’s when the import of what had happened fully hit daddy and Dudley.

Earlier that same day, Gus had gathered together Sam and Alice and told them that he did not have any money to pay them and that they would have to find other work. Sam and Alice exchanged a look (it seems that they had spoken about this and were prepared) and told my grandfather that they would not abandon the Oldhams, that they were their family now and that they would stay with the family in the little shack. Sam made the case that he could find work that a white man couldn’t find, and that Alice could take in laundry and ironing.

So, that bleak day when they drove away from the big house in Beaumont, Alice and Sam were stuffed in the car along with Gus, Angeline, Dudley, and Harold. They all lived in that shack in deep east Texas for three years, during which time, Alice and Sam were virtually the sole support of my family. Sam did find work and Alice did take in laundry. Alice and Sam slept in the kitchen. The boys slept in cots on the screened-in porch, and daddy talked about cold nights when the snow flew in through the screens, whereupon he and his brother would dust the snow from their blankets and go back to sleep. I think that this is why my daddy could sleep almost anywhere, at any time, for the rest of his too-short life.

Daddy and Uncle Dudley called Saturday night “tight-shoe night.” They had one pair of dress shoes between them and would alternate Saturday night dates so that they could wear decent shoes to impress the girls. They were tight shoes because their feet were still growing, but there was no money for something as frivolous as new shoes. Eventually, Gus worked his way out of the Depression and the Oldham Lumber Company thrived once again. In fact, my grandfather made and lost several fortunes over his lifetime. But that’s a story for another day.

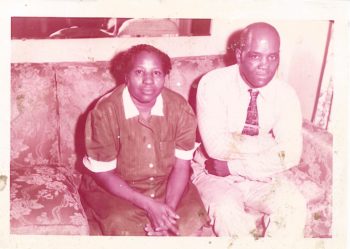

Happily, for my sister and me, Alice and Sam never left the Oldham family. I was an anxious child and did not like being separated from my mother and father. I was unwilling to spend any time with either set of grandparents, if they wanted to take me away from my own house, so my relationship with them was never fully realized. Alice and Sam, however, came to my house and were the only babysitters that I wanted. I loved them with my whole five-year-old heart, even telling my parents that if something happened to them, I wanted to go to Alice and Sam. I made them promise to write that down. I was deadly serious. Alice and Sam understood me and gave me unconditional love, and I felt secure and protected in their presence. They never had children of their own, so they embraced us as their family.

One day, around that time, my mother and I went to the bus station in Houston, which was an exciting outing for me. We had never been to the bus station, a grand edifice in the days of such kind of bus stations, and we were picking up an old friend of mother. When we entered the marble waiting area, I saw a sign that thrilled me. I let go of my mother’s hand and ran across the entire span of the lobby, screaming, “Mommy, mommy, look. Rainbow water is in that fountain. Let’s go look at it.”

Mother ran after me, trying to slow me down and shush me up, to no avail. I kept a blistering pace and got to the fountain, mashed the button, and out came…water, plain old water. No rainbows. No colors caught in the light. Why did they put that sign, “Colored” over the fountain? It made no sense.

Poor mother. Every eye in the bus station was on us as she tried to calm me down and explain what it meant by “Colored.” When it finally dawned on me what she was saying, I was no longer sad. I was baffled. Weren’t Alice and Sam colored? Alice and Sam, for Pete’s sake! They were more grandparents to me than my own flesh and blood. Why would we possibly need to separate them when they drank water? Alice, who combed my hair and watched over me and cooked everything I liked, and Sam who sat by us, his quiet, steady nature providing us a veil of security, resided in a place deep in my heart, a precious, unassailable place.

When our friend arrived, I was still spewing furious questions at my poor mother, until she convinced me that we would talk about it later. We did talk about it later, and talked some more. There was nothing she could say to make sense of the nonsensical. If this dumb rule applied to Alice and Sam, then it was a rule that was plainly wrong. In my child’s brain, I knew that, as surely as I knew up from down.

From that terrible day to this, changing that abhorrent rule and all the abhorrent rules that determined the fate of black people in America and our relationships with one another became my personal guiding principle. One of Alice and Sam’s greatest gifts to me was that they allowed me to see the world through their lens, not as employees, as some might accuse, but as fierce and proud and accomplished and beautiful members of my family. I do not presume to be able to tell Alice and Sam’s story, to co-opt their story as my own. I know they suffered indignities in their lives that would horrify me. But I also know that love we had for each other was pure and clear and full of grace and is a profound part of my story.

As I grew older, I realized that it is not as simple as tearing down a sign that said “Colored.” It is more primal. We must tear down walls and misunderstandings that reside in our hearts and in our laws and in our behavior. We are not there yet. Not nearly there.

We break through one wall and find that four more have popped up in its place, but that five-year-old girl will never stop trying until all that a “Colored” sign over a water fountain means is that shimmering, bright, rainbows of water will come gushing up out of it and bestow us with justice rolling down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream, at last.

Marguerite Williams

Marguerite (Margo) Williams is a novelist ("Madame President"), editor, and business owner of A Way With Words. She has lived in Davidson since 1977. Visit her at her website.