DAVIDSON HISTORY

Native Americans in Mecklenburg County

During the late nineteenth century, occasional newspaper reports appeared detailing sightings of the remnants of the area’s Catawba Indians. In 1886 the Charlotte Chronicle mentioned the appearance of three Catawba in Charlotte. According to the Asheville Citizen, which cited the Chronicle, “We thought they had all gone. These must be a feeble remnant…it is a long time since we saw any of the Catawbas, and we believed, until now, that they were extinct.” In January of 1893, an article datelined Davidson appeared in Winston-Salem’s Western Sentinel. The correspondent noted that “A band of Indians, nine in number, showed here recently.”

These sad remnants were all that was left of a once-populous nation. Early Native Americans, referred to as Paleo-Indians, originally came into North America from Asia 40,000 years ago. They were nomadic, and following the end of the last ice age around 11,500 years ago, crossed the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains in pursuit of the giant mammals, including mammoth, horses, camels and bison, then living in the North Carolina Piedmont. One of their campsites was located at The Big Rock on Four Mile Creek in southern Mecklenburg County.

The descendants of these early Native Americans are now known as Archaic Indians. As the Ice Age ended, the forests began to change and soon resembled those of today. The Archaic Indians were still nomads, fishing and hunting game with their spears, and also gathering food and raw materials for shelters. They traded with their neighbors and may have used dugout canoes in their travels. They lacked many of the items of later indigenous peoples, including bows and arrows, and they did not rely on agriculture.

About 2000 years ago, these tribes began to establish semi-permanent settlements along streams and rivers and practice agriculture. Among their crops were maize (corn), tobacco, beans, and squash. They developed a sophisticated culture and practiced a polytheistic religion. They had no idea of private property; they used the land but did not divide it into private plots. By this time, they used bows and arrows to hunt deer and turkeys.

These Woodland tribes had a complex system of trails that they used for trading. Two of these trails, the Tuckaseegee Trail and the Great Trading Path, intersected in the center of what is now Charlotte, and greatly influenced its growth. The Trading Path extended through the Piedmont from Virginia into South Carolina, following roughly the present route of I-85. The Tuckaseegee Trail extended from the center of Charlotte to the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, crossing the Catawba River at the Tuckaseegee Ford, the first documented river ford in Mecklenburg County. The first explorers and traders in the region made extensive use of these trails to bring in goods, which they traded for animal hides.

When European explorers began to arrive in the area, they encountered a number of tribes. While we think of the Sioux Indians as being a Western tribe, these Carolina tribes were also Souian, and are referred to as Eastern Sioux or Souian-Catawban. In contrast, the Cherokee actually were related to the Algonquin, who originated in Canada. When European exploration began in the mid-1500s, the population of one local tribe, the Catawba, was estimated at over 8,000.

One of the earliest explorers to reach the Catawba River was a Spaniard, Hernando de Soto, who arrived in May of 1540. Along the Catawba, just southwest of Charlotte, he encountered the Xuali tribe (known today as the Cheraw). De Soto’s expedition probably introduced European diseases like smallpox, which were to decimate the Native American population in years to come. The next major expedition, that of John Lawson in 1701, was the first to thoroughly explore the North Carolina Piedmont. In the northern parts of the Piedmont, he encountered only scattered native villages, already ravaged by smallpox. In the lower Catawba valley, however, he encountered the thriving villages of the Esaw Indians, now known as the Catawba, which he described as “a very large Nation containing many thousand People.”

A rare image of the Catawba at the 1913 Corn Exposition in Rock Hill

The Catawba ( who called themselves “yeh is-Wah h’reh” or “people of the river”) occupied more of North Carolina than any other tribe, and their settlements along the Catawba River extended into South Carolina. They lived in villages enclosed by wooden palisades. Inside this wall there was a council house, a sweat lodge, and small rounded dwellings made of bark. They were fishermen, hunters, and farmers, planting crops like corn and squash in soil that Lawson described as “red as blood.” Their custom was to bind the foreheads of male babies, giving them the look of a flat forehead. The Catawba were fierce warriors, and during warfare with neighboring tribes, they painted their faces black and circled one eye with white paint.

Lawson stayed for a time with the Waxhaws or Wisacky, another Siouan tribe that lived along Waxhaw Creek in southwestern Union County, N.C., and also in Mecklenburg County and Lancaster County, S.C.

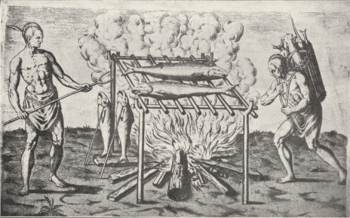

This historic illustration of the Waxhaw, along with other artifacts representing the tribe, is on display at their museum in – where else? – Waxhaw, N.C.

He noted that the Waxhaws were very welcoming. They shared the Catawba’s rituals and architecture. He described them as very tall, with the men having the same flattened heads as the Catawba. Their tribal councils and dance ceremonies were held in a large council house, thatched with sedge and rushes. He later encountered the Sugeree, who were living in a string of towns and villages in a fertile region along present-day Sugar Creek, which is named for them.

Trade had already begun to impact Native American life by the late 17th century. The various tribes traded deerskins to the Europeans in exchange for goods like knives, kettles, cloth, and muskets, and the villages became major trading centers. When European settlers began to move into the Piedmont in the early 18th century, the tribes welcomed them.

By 1713, however, Native Americans had become enraged by the actions of Indian slave traders and dishonest fur traders. The Catawba joined with the Yemassee, who lived on the coast in northern Georgia, in attacks against settlers in the lowcountry of South Carolina. The natives were soundly defeated, and the depleted forces of the Catawba retreated north. The smaller local tribes, including the Cheraw, the Waxhaw, and the Sugaree began to join the Catawba for their own protection. Despite these additions to the tribe, disease and warfare had reduced the number of Catawba to 1,400 by 1728. In 1738 smallpox struck again, killing nearly one-half of the of the remaining members.

During the 1750s the Catawba were attacked by war parties from the north, and several years of drought ruined their crops. They fought on the side of the colonists in the French and Indian war, and regained some strength, but another smallpox epidemic in 1759 reduced their numbers to 500. That year they consolidated into a town at Twelve Mile Creek, which crosses the North Carolina/South Carolina border not far from Waxhaw. By 1760, there were only 60 fighting men in the whole tribe. By the time the French and Indian War was over in 1763, the British colonies had no more use for their Catawba allies. The British gave the Catawba 15 square miles on both sides of the Catawba River in present-day Lancaster and York counties, South Carolina, and the tribe relocated.

During the American Revolution, the Catawba fought on the side of the colonies, engaging the Cherokee and Lord Cornwallis in North Carolina. After the British captured Charleston in 1780 and began to move north, the natives once again moved up into North Carolina. When they returned to the reservation in 1781, they found their village devastated. By 1826 only thirty families, comprising a little over 100 people, were living there, and the land was soon leased to non-natives.

During the 1840s, following the plan of the Trail of Tears, which had moved the Cherokee west during the previous decade, there were efforts to resettle the Catawba near the Cherokee. When this failed, they were settled on 630 acres on the west bank of the Catawba in South Carolina. According to newspaper reports, while some of them had moved back near the remaining Cherokee in North Carolina, those on the reservation were in a “prosperous condition,” with the state of South Carolina supporting them with annual appropriations and supplies. But due to declining numbers, by 1846 they had ceded all but one square mile of this land and moved to western North Carolina.

According to the May 22, 1846 edition of the Carolina Watchman, James Kegg, described as the principle chief of the Catawba, had recently appeared before the U.S. Congress to present a petition. According to Kegg, the Catawba had “recently removed from South Carolina to North Carolina; that they now own no land; that remnant of the once powerful Catawba tribe is now reduced to eighty-two souls. They humbly ask Congress to make arrangements and adequate appropriations to remove them to the west of Arkansas, and give them a home in the woods.” The paper commented that “A great people, sovereigns of a large portion of this broad land, flourished until they came in contact with civilized man; and then, instead of improving and prospering by the association, commenced their downward career. The more enlightened white men supplied them with fire-water, which killed them by thousands, induced the survivors to part with their lands for a song, and finally brought them to the above sad state…mendicants, humbly asking Congress to give them a home in the woods anxious, doubtless, that that home may be as far removed as possible from the blessings of such civilization as it has been their misfortune to encounter.”

Discussions of removal continued in both the North Carolina Legislature and the U.S. Congress until 1849. The tribe was never moved west, however, and in 1850 South Carolina again sold them land, and they returned there. In 1858 the agent of the Catawba in South Carolina reported only 70 living on the reservation. He went on to say that “I cannot discover any improvement in their moral condition or habits; in general they are fond of spirituous liquors; and there are now two distilleries near them, and when they earn a little money…they will spend it for whiskey, and get drunk, and sometimes do mischief.” He referred to the situation as “a sad nuisance in a civil community.” “I have had but little conversation with the Indians this year about removing to the West, but so far as I have learned, they are still willing to be removed.”

Some members of the tribe fought in the Seventeenth South Carolina Regiment during the Civil War. By 1882 the population had increased to 95, but soon afterwards Mormon missionaries lured a number of them into moving to Colorado. By 1895, there were only 55 tribal members remaining. In 1900, a monument was erected in Fort Mill to honor those who served in in the Civil War. During the early twentieth century, heavy rains often revealed bones and relics of the original Catawba population along the Catawba River near Charlotte.

The Catawba became a federally recognized tribe in 1941, but in 1959 ended their tribal status. They received individual landholdings three years later. At that time tribal membership was around 600. This action, however, did damage to their cultural identity and decreased their ability to maintain a community. They then began the fight to regain their status. In 1973 they reorganized their tribal council, which led to recognition by the state of South Carolina. In 1993, after a prolonged court case, they regained federal status and began to establish a tribal roll. This was accompanied by a state and federal settlement. The tribe now boasts around 2800 people, still a fraction of their original population.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.