NEWS

A Forgotten Davidson Neighborhood

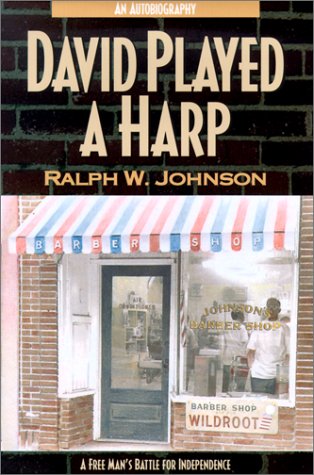

“David Played a Harp: A Free Man’s Battle for Independence” by Ralph Johnson, published August 1, 2000

Today we think of Davidson’s African American neighborhood as being on the West Side. Over a century ago, however, there was another Black neighborhood located north of Davidson on an unpaved road that is now US 115. In his book David Played a Harp, Davidson barber Ralph Johnson gave a detailed description of the neighborhood, including its diverse and interesting group of residents.

The neighborhood was divided by the highway and the railroad into east and west sides. The first of five houses on the east side, entering from the north, belonged to Furman Brody. Brody, who was born into slavery, was not only a Presbyterian pastor, but also conducted a school for African Americans. He and his large family lived in Davidson until he left to go to Morganton in 1913. Johnson describes him as “a tall, brown-skinned man” who was always smiling. He adds that “He was highly regarded by everyone, and even some white people called him Reverend Brody, but most of them just called him Brody.”

Next in line was the house where Ralph Johnson was born in 1904. Ralph was the son of Walter Johnson, one of the first Black barbers in Davidson. The Johnson family was fairly prosperous, and when Walter died in 1912, he owned his own home, a barbershop in which he employed two barbers, and a rental property on the West Side. Over the years, he was able to add on to his small dwelling and install telephone service. Ralph, his mother and his sister Ervin continued to live in the house until 1934 when the house was burned to the ground. They then moved to Walter’s former rental property.

The land rose just south of the Johnsons’ house, and located on this higher ground was the house of James F. “Fess” Connor and his wife Lizzie. The Connors had no children, and in 1910, James was working as a laborer and Lizzie as a cook in a private home. They believed in “root walking,” which held that someone could poison them by putting something under the ground that they would walk over. As a consequence, their property was surrounded by a four-foot fence, and their well was fortified against any possible intrusion. According to Johnson, “The Connors had no company, nor did they visit in the neighborhood.”

South of the Connors lived a white family, Moses M. “Mose” and Maggie Hampton and their three children. In 1910 Hampton had a livery stable, and by 1920 he had a business as a transfer driver. One of Mose’s wagons was actually involved in a collision with a car in 1917, the first auto accident in Davidson. According to Johnson, “They were friendly people, and Mrs. Hampton and Mama were friends. I played with the Hampton children, and we have remained friends through more than sixty years.”

South of the Hamptons’ home was another white family, headed up by Homer B. Mayhew and his wife Iva. Although Johnson remembers him as the Singer sewing machine agent, in 1910 he worked as a farm laborer. By 1920, he had settled in Coddle Creek Township in Iredell County and owned his own pressing club. In 1930, he ran a café there. By 1940, he was a salesman in Mooresville, and in 1954 he was the proprietor of Mayhew’s sewing machine shop there. Johnson remembers his mother buying her last sewing machine from Mayhew when she was 80 years old.

Across the road and railroad tracks from the Johnson’s home was the home of another white man, Mack Brown. His property covered more than five acres, and Johnson remembers reading under a tree and being constantly entertained (and enlightened) by Brown’s language. He had an ornery mule named Jack, and, according to Johnson, when he got frustrated with Jack, he belabored him with his “colorful language,” reaching “heights of anger and profane language hitherto unknown to me.”

Just north of the Browns lived the Byers family. Andy Byers was a blacksmith and had his business on his rather ramshackle property. In addition, he was responsible for the town’s “sugar wagon,” used to empty privies around Davidson. This wagon was “an ancient, decrepit four-wheeled one-horse wagon,” drawn by yet another stubborn mule named Jack. Byers, too, got frustrated with his mule, but his response was very different from Brown’s. Rather than curse at Jack, he prayed, getting louder the more difficult the mule became. Soon, loud cries of “Gee, gee. O, Lord have mercy. GEE! GEE! GEE!” were mixed with Brown’s profanity. Johnson found it very entertaining when they plowed on the same day. Andrew Byers had an interesting history. His father, Andrew Byers, was a slave, probably owned by James Smith Byers of Iredell County, who was a carriage driver and a skillful violinist.

The northern end of this side of the neighborhood was occupied by six three-room houses built by Davidson College professor and President John Shearer and rented out to black families. One of these families was that of Stewart and Lizzie Heiligh (identified in census records as Lizzie Heilige). Lizzie was a skilled midwife, whose practice was limited almost exclusively to the “better-class” white families in town. Her services were expensive for the time; she attended the birth and then spent a week with the family, helping with cooking and washing, all for $3.00!

It enriches Davidson’s history to have books like Ralph Johnson’s book. Without it, we would have little anecdotal information on black life in town during the early Twentieth century.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.