NEWS

The Great Depression in Davidson

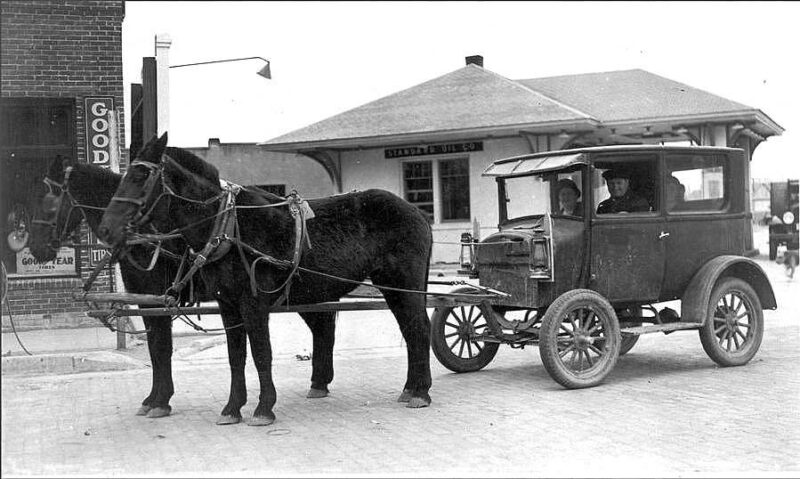

Hoover Cart

We usually think of the Great Depression as beginning with the stock market crash in 1929, but its roots go further back in rural agricultural areas, especially in the South. During World War I, when demand for agricultural products grew in Europe, farmers prospered. Once the United States entered the war, the government guaranteed food prices in order to supply the army. Farmers began using borrowed money to buy additional acreage and increase their herds. When the war ended and farm prices dropped, farmers were unable to repay their loans and the banks foreclosed. By the official beginning of the Great Depression in 1929, the South’s per capita income was around 50 percent of that in the rest of the country, making it the poorest region in the U.S.

On October 29, 1929, the U.S. stock market crashed, and stock prices dropped 30% in a week. Herbert Hoover, who had come into office that spring, faced a grim situation. In his book “Memories of Davidson College,” Walter Lingle, who became president of Davidson College that summer, noted that “President Hoover and I hit upon evil times. We both entered office in 1929, the year of the great financial crash…I had not been at Davidson two months before the crash occurred on Wall Street and we entered into the most disastrous financial depression this country has ever known…when the financial crash came there was no use to talk about raising any considerable sums of money for anything.”

The crash also had serious repercussions in the town of Davidson. In his book “David Played a Harp,” Ralph Johnson noted that “By late summer of 1930, the ever-deepening effects of the Great Depression were becoming increasingly apparent. Shadows of impending doom were gathering everywhere. Money had grown scarce. Unemployment was a continually rising apparition of further and more wretched times ahead. Business in the barber shop was in a decline…A forlorn atmosphere of defeat had crept into the thinking of many people as the situation worsened.”

Johnson noted that cotton prices had fallen drastically, and more and more people were unemployed. Indeed, “The Depression wouldn’t go away. Its tentacles grew longer and longer and wound themselves tighter and tighter around the throat of the economy.” By early 1931, “there were many men … who a year or so earlier had been in a condition of some affluence but now found themselves hardly able to pay for a twenty-five-cent haircut.”

Like many other shop owners at the time, Johnson’s solution was to set up a system of barter, accepting such things as “eggs, chickens, chunks of fatback, hams, meal, black walnuts, hickory nuts, peanuts, molasses, blackberries and whatever else they had to trade. There were times when the goods brought in were in excess of what was needed to pay for present haircuts. In those cases, they were left as deposits for future use by the persons bringing them, or for their friends…During the hunting season, rabbits…were brought in in such large quantities that at one time this meat was a staple food item on our table in winter.” While these contributions kept his family well supplied, they did nothing to defray his expenses for rent, electricity, water, and salaries for his barbers.

Farm prices, including cotton prices, continued to fall. National farm income in 1932 was less than a third of what it had been in 1919. Farmers continued to lose their homes and farms. Banks continued to fail, and by 1932 over 200 banks across North Carolina had closed. 25 percent of Americans were unemployed, and the stock market had fallen 75 percent from its 1919 values.

By 1933, farm income in North Carolina had dropped 50 percent and wages in the cotton industry had dropped by 25 percent. People everywhere were in need of food and clothing. Those who had luxuries like cars began transforming them into “Hoover carts,” which were drawn by horses. Formerly wealthy farmers were left with rotting cotton that they had declined to sell for the low prices being offered before the Depression.

Franklin D. Roosevelt became President in March of 1933 and, among an increasing number of bank failures, declared a bank holiday to temporarily stop runs on banks. That same year North Carolina’s Commissioner of Banks was given the authority to declare a bank holiday and was allowed to limit withdrawals. In 1934, however, Ralph Johnson noted that “The Depression was still very much with us… The effects of financial disaster were all around. The state of mind of everyone was depressed. Farms and homes were being lost. Businesses continued to go into bankruptcy. Main Street had almost the appearance of a ghost town with so many empty store buildings. Money was extremely scarce, despite President Roosevelt’s Herculean efforts to get the economy back on its feet.”

The Davidson Colored School, now the Ada Jenkins Center.

In 1933, as part of his New Deal, President Roosevelt established the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works (later the Public Works Administration), one of the New Deal programs used to recruit millions of unemployed Americans to work on both large and small public projects, like roads, municipal buildings, courthouses, airports, parks, and school improvements. Davidson was the beneficiary of some of these funds when the Mecklenburg County school district used them to underwrite 45 percent of the construction of a gymnasium at the Davidson School. The building, designed by Charlotte architect Willard D. Rogers, was completed in 1937. At the same time, Rogers designed a building for the Davidson Colored School (now the Ada Jenkins Center), and a new 12-room school in Cornelius. Both were partly funded by the Public Works Administration.

Davidson College was also suffering during this period. In what Walter Lingle called “a time of general demoralization,” his efforts turned to trying to “keep the morale of the faculty and students from breaking.” By 1934, the yield on the endowment, had fallen from $50,000 to $35,000 per year. Church collections had decreased by a third, and yearly income from the Duke Endowment by $10,000. Fewer high school students could afford college, and those who could come required more financial aid. Although times remained tough for seven years, he managed to keep the college intact and hang onto its faculty, while running no deficit.

However, the college was forced to temporarily lower its admission standards, which resulted in a reduction in academic standards. New entrance requirements included only a high school diploma and the “necessary number of entrance units.” Class standing was not taken into account. According to Lingle, “we have to work right industriously to keep our student enrollment up to the present mark.” Admissions standards began to rise in 1935, and academic standards by 1937. Things were also improving on Main Street, and by 1938 Ralph Johnson was able to report that business at his barber shop was picking up.

Despite some improvement in the economy, the Depression continued. Between May 1937 and June 1938, there was a “double-dip recession,” which caused the gross domestic product to fall 10 percent and unemployment to reach 20 percent. In 1939, a woman living in the North Carolina mountains reported that, although her husband had a job through the federal Works Progress Administration, “we haven’t had anything in the house to eat for a week now but two messes of flour and a peck of meal. The children has nothin’ for breakfast but a biscuit or a slice of corn bread. They come home after school begging for food. But I can’t give them but two meals a day…I ain’t got but one sheet, no pillow cases, and only one towel.” (ncpedia.org)

That same year, however, President Roosevelt decided to support France and Britain in their fight against Germany, and defense manufacturing increased. Only when the United States entered World War II in late 1941 did factories resume full production and the economy improve further. This, combined with the 1942 establishment of the military draft, finally brought the unemployment rate to under what it had been in 1929. After more than a decade of suffering, the Great Depression was at an end.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.