NEWS

Lake Norman, once Described as “The Many-contoured Lake that is to be Proven a Joyous Haven for Happy Families in its Season”

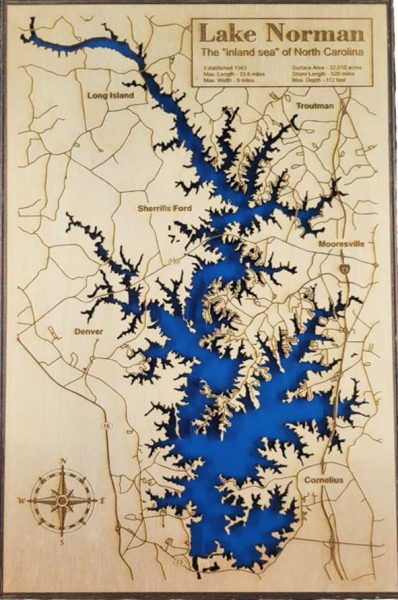

When it is summer in Davidson, for many of us life centers around North Carolina’s “inland sea,” Lake Norman. When we moved to Davidson in 1979, the lake had been in existence for 26 years, and I-77 had been open for four. The new lake, which resulted from flooding the Catawba River valley, bordered four counties: Mecklenburg, Iredell, Lincoln, and Catawba. To us, these were settled realities, and I never thought about what came before. Recently, however, I was reading Olin, Oskeegum & Gizmo, James Puckett’s memoir of growing up in Davidson, and I began to wonder what had occupied the land before it was inundated.

Duke Power had a vision for an industrialized South, and Lake Norman, named for onetime Duke Power president Norman Cocke, was the last of eleven lakes to be built along the Catawba River. The company began acquiring property in the area around 1910, leasing some of it back to the farmers to cultivate, and purchasing the rest outright for between $80 and $1000 an acre. During the Great Depression, which started in 1929, this process accelerated. Some sold most of their land and retained the property that would be on the lakefront, sensing it would be valuable. These families either moved to other farms, or into area towns. Work on the Cowan’s Ford Dam commenced on September 29, 1959, when Governor Luther Hodges blasted the first rock from the riverbed. A report on the event published in the Mooresville Tribune noted that Governor Hodges talked about the “great courage and vision of the men who founded the Duke Power Company and hundreds of others who had faith in the future of electric power at a time when such faith was at a premium.”

Norman Cocke put forester Carl Blades in charge of making the land ready for the water, and Blades went out into the bottom lands bordering the Catawba River to buy acreage. In a 1982 interview, Blades remembered the daunting task of purchasing more than 30,000 acres of family farmland for Duke Power’s Lake. “I spent many days and nights in this area,” he remembered. “We ran into a few difficulties in the negotiations. People were reluctant to sell their family homes where many had lived for generations.”

According to Barbara Russell’s March 2004 article in the Lake Norman Magazine, however, “Many residents might not necessarily have been happy about being displaced, but there weren’t any huge protests. Some even turned the burden into a boon. Some savvy farmers held onto what would become pricey lakefront property. And there are a few people who refused to sell, but instead merely leased the water rights to the power company.” According to Cindy Jacobs’ June 18, 2013 article in the Hickory Daily Record, Duke Power also began leasing one-acre lakefront lots to interested parties for $120 per year. Blades and his men accompanied these future owners through farms and woods to select their lots. The future residents soon began to spend their weekends building cabins and piers along the projected high-water mark of the future lake. By 1962, when the dam was finished, Duke Power had made more than 2,500 cottage sites available via lease to the public.

Much was lost as the waters rose. The land along the Catawba had long been occupied by Native Americans, who grew corn, squash, and beans in the rich soil along its banks. These ancient residents, whom we refer to as the Catawba Indians, roamed the land as long ago as 10,000 years. Flooding the river bottoms for the lake resulted in the inundation of around 400 archaeological sites, containing mostly artifacts from the Woodlands Period, 3000-500 B.C.

In the mid-1750s, white settlers began coming into the area on the Great Wagon Road, which extended to North Carolina from Pennsylvania. These families, including the Beatties and the Sherrills, occupied the land and used the shallow river crossings as fords, later named in their honor. These farmers and many others, sometimes with the help of slaves, produced corn, cotton, wheat, and watermelon. They built roads, bridges, and homes, some of which were grand in scale. All of this, including grand homes like John D. Graham’s plantation in Denver, was threatened. The Graham House was eventually disassembled and sent to Winston-Salem to be rebuilt, but everything flammable was destroyed in a fire there. Many smaller houses and farms also disappeared in the rising waters of the lake.

There was also industry along the river. Notable among these enterprises were the Long Island and East Monbo cotton mills, just across the river from each other in Catawba and Iredell counties. Long Island mill, built in the 1850s, was one of the earliest mills on the river; East Monbo was built in 1907. Both mills provided housing for their workers in mill villages built near the river. When plans for the lake were being finalized in the early 1950s, workers were given the option to own their homes free of charge if they could afford to move them elsewhere. Costs being prohibitive, few could afford to move them. Others traded their land for property that eventually became lakefront. What remained of the mills and villages was eventually drowned in the lake.

There were other repercussions, as well. As James Puckett noted, “Entire cemeteries were relocated, and this had ghoulish repercussions. There were all kinds of complaints raised about mishandling of caskets and corpses.” Among those moved were the Baker Cemetery and the Clark family cemetery, which included graves dating from 1813-1875. The Hunters Chapel A.M.E. Zion cemetery, with graves from 1813-1865, was relocated to the new Hunters Chapel church grounds in Cornelius. Camp Fellowship, which was opened by the Barium Springs Orphanage in 1938 and later taken over by the First Presbyterian Church in Mooresville, was inundated.

Other small losses occurred. James Puckett bemoaned the demolition of the bridge at Beattie’s Ford which destroyed their old swimming hole, distinguished by “large rock outcroppings and deep pools,” a spot that had been used as such back in colonial times. Puckett remembers riding his bike to an observation post near the new dam where residents could monitor developments. Bettie Liffrig told Barbara Russell that she watched from this observation post and remembers how desolate the dried-out lakebed looked: “It was so barren, see, with all the trees and buildings gone…it was just a desert out there.” Such a difference from the forests, fields and homesteads that once dotted the valley.

By late in the summer of 1963, Lake Norman had reached full pond. It covered over 32,000 acres and was the largest lake in North Carolina. Duke Power still owned 50% of the lake’s 500-mile shoreline. A 1965 Duke Power map of the lake showed that the remainder of the shore remained sparsely occupied. According to Charles McShane’s 2013 article in Charlotte Magazine, there were two restaurants, two grocery stores, and eight places to get gas. Development continued, however. Buck Teague opened a campground and marina named Outrigger Harbor at the site where the Peninsula Yacht Club now stands. It also provided rental cottages, known as the “Boatel,” areas for swimming and fishing, boat rentals, and picnic sites. For many years it was home to the Kon Tiki dinner boat and a paddle-wheel tour boat.

Donna Campbell, whose family rented one of the early lots along the lake, wrote for Our State in 2013 that other marinas soon followed, including Oni’s Landing, Country Corner Marine, Commodore, and Wher-Rena Marina. Her family owned John’s Landing and John’s Trading Post, described as a “Dealer in Most Everything.” According to Campbell, “This meant we sold both night crawlers and caviar. People brought their fish in to be weighed, and we took photos with a brand-new Polaroid camera.”

Enjoying the lake sometimes held surprises for the uninitiated. According to James Puckett, as soon as the lake was filled, “Charlotteans began coming out in droves to overuse this lake just as they had overused nearby lakes along the Catawba system. This time they were in for a surprise. Engineers had cleared the land that would be the lakebed, but as the lake filled, debris kept surfacing. There followed a rash of serious and sometimes fatal boating and water-skiing incidents.”

Soon housing developments like Moonlight Bay, Isle of Pines, Kiser’s Island, Island Forest, and Westport began to appear, providing second homes for people from Charlotte and surrounding communities. The lake was also a prime hangout for local people. According to Charles McShane, during the early days “Mooresville teens raced on the cleared roadbed that would become I-77, then found a place off N.C. 150 to cool off in the water, leaving their cars on the roadside, caked in red clay.” You could swim anywhere, with few private docks and developments.

But with the completion of I-77 in 1975, the lake became accessible to people from all over, and construction soared. Duke Power, through its subsidiary Crescent Resources, began to sell some of its land along the lake, and the population grew. No longer just a place for second homes, the lakeshore became an easy commute from Charlotte, and more permanent homes were built. According to James Puckett, “After the interstate connected the area to Charlotte in 1975, the trickle of growth—a cluster of cabins here, a new marina there—grew to a steady stream of homes and restaurants. The lake wasn’t just a weekend destination anymore. It was now an easy commute to and from an uptown office tower.” Almost 50 years later, the shores are crowded and local towns have grown beyond most peoples’ imaginations.

At the 1959 groundbreaking for the Cowan’s Ford Dam, Bishop Nolan B. Harding’s prayer expressed his hopes for the future lake:

“”Bless this lovely countryside now to be changed by the inflowing of water. May the land lost prove prosperity gained, and the valleys that can no longer sing with corn, sing through lofty wires, that carry their strength to far off places. Let the many-contoured lake that is to be prove a joyous haven for happy families in its season, be nature’s refuge for fish that swim and birds that fly, its surface reflecting with untroubled face the peace of quiet and holy skies.” It is ours to decide if this promise has been fulfilled.

Note on sources: The most comprehensive source of information on Lake Norman is the “Under Lake Norman” page on the Davidson College Archives website. It includes many articles, including some that I’ve quoted here, as well as photos, maps, and lists and histories of the sites that were originally in the lakebed. The sources I’ve quoted are listed below.

Donna Campbell. “History of Lake Norman.” Our State. Originally published in 2013. Available at ourstate.com.

Cindy Jacobs. “Bold Plan Took Shape in 1957.” Hickory Daily Record, June 18, 2013.

Charles McShane. “A History of Lake Norman.” Charlotte Magazine, July 26, 2013.

James B. Puckett. Olin, Oskeegum & Gizmo. 2002.

Barbara Russell. “The Lake that Changed the Landscape.” Lake Norman Magazine, March 2004.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.