NEWS

When Dancing Finally Came to Davidson College

It may have seemed strange to read about the prohibition on dancing in Davidson described in the accounts of Lucy Phillips Russell and her Aunt Cornelia Phillips Spencer. In our modern minds, dancing is accepted as an innocent pastime and enjoyed by almost everyone. For over 100 years, however, Davidson College struggled mightily about permitting dancing on campus. The college was founded by Presbyterians, and, especially in the early years, most of the professors and townspeople were Presbyterian. Their stance was based on the earliest doctrines of the Presbyterian Church. John Calvin himself insisted that church members in Geneva who danced should be punished. The Westminster Catechism condemned “lascivious” dancing as contrary to the Seventh Commandment.

It may have seemed strange to read about the prohibition on dancing in Davidson described in the accounts of Lucy Phillips Russell and her Aunt Cornelia Phillips Spencer. In our modern minds, dancing is accepted as an innocent pastime and enjoyed by almost everyone. For over 100 years, however, Davidson College struggled mightily about permitting dancing on campus. The college was founded by Presbyterians, and, especially in the early years, most of the professors and townspeople were Presbyterian. Their stance was based on the earliest doctrines of the Presbyterian Church. John Calvin himself insisted that church members in Geneva who danced should be punished. The Westminster Catechism condemned “lascivious” dancing as contrary to the Seventh Commandment.

While that commandment expressly forbids adultery, it was expanded to forbid all enticements to sins of the flesh, including mixed dancing. The Scotch Assembly of 1649 noted the “scandal and abuse that arises through promiscuous dancing” and denounced the habit, suggesting censure. In 1789, members of the Synod of North Carolina, responding to an overture presented to them, suggested that members involved in dancing and gambling should be dealt with by “their spiritual rulers.” The General Assembly of 1818 denounced dancing “in its highest extremes,” saying that it would be apt to lead to “fatal consequences.” The Assembly saw “danger from its incipient stages” and asked church members to “heed on this subject the admonitions of those whom you have chosen to watch for your souls.”

The Davidson College church adhered to this policy, and in 1838 the session interviewed a college student when it learned that he “had taken some part with a company of youths in dancing.” He acknowledged his sin, gave a sincere apology, and was allowed to remain in the church. In 1844, a female member of the church also violated the policy, and the session asked the pastor to admonish her. Following the split between the Northern and Southern Presbyterian churches in the 1860s, the General Assembly of the Southern church left it up to individual churches “to make deliverances affirming their sense of what constituted an offense,” and declared that dancing was “in direct opposition to the Scriptures and our standards,” was indisputably a “worldly conformity,” and was liable to “excesses.” Pastors were to instruct from the pulpit and admonish offenders. If this failed the session was to conduct “such methods of discipline as shall separate from the church those who love the world and whose practices confirm thereto.”

By 1871, students were apparently weary of this proscription and tried to organize a commencement ball in Charlotte. The faculty voted unanimously that it regarded the plan “with the most decided disapprobation.” Individual students were also wrestling with this problem. In 1876, a Davidson student named Henry Fries wrote to his sister that he was giving up dancing, which he loved, because “though it appears as innocent amusement there is much harm in it, for it carries one’s mind from solemn considerations to a life of worldly things…”

In May 1878, the Charlotte Observer reported on anther proposed commencement dance to be held at Charlotte’s Central Hotel, noting that “a large number of invitations have been issued, and the ball promises to be a brilliant affair.” The First Presbyterian Church in Charlotte contacted the college about the matter, and the Clerk of the Faculty was “directed…to assure the Session that we will be glad to cooperate with them in averting the evils apprehended.”

By 1883, there must have been Davidson dances in Charlotte, because in a “Raleigh Letter” published in the Charlotte Observer in February, a correspondent noted that those at Chapel Hill wanted a new gymnasium at the University of North Carolina, partly to provide a place where dances could be held on campus. The article went on to opine: “It would never do to drive the students off the grounds for dancing, the Presbyterians object to dancing at Davidson college and yet the students go to Charlotte and do their dancing, and so the Chapel Hill students would come to Raleigh and do theirs, where bar-rooms and other temptations surrounded them.”

Despite the College’s regulations, Davidson students continued to dance in Charlotte. Local newspapers mention a sophomore dance at the Selwyn Hotel in February 1908, and a dance given by the Davidson College Cotillion Club in Lakewood Park in late May of 1913. Apparently, this latter dance was an annual affair, and, according to the Charlotte Evening Chronicle, “Practically the entire body of young ladies in attendance at commencement exercises will come down for the [sic] tonight’s dance.”

In November 1916, there was a Thanksgiving night dance in Charlotte following the Clemson/Davidson football game, and in early March of 1918 a dance was held in Charlotte following the annual junior speaking, an event which promised “to be one of the largest and most successful

1920s Illustration of a Tango Lesson

Davidson dances yet held.” That same year the college’s trustees reminded students “with great kindness, and yet with great earnestness that the Board of Trustees cannot approve of dancing on the Campus or in connection with the College in any way.”

Dances in Charlotte continued, however, including one held in March 1919, which was sponsored by the St. Cecelia Club and was to last from 9 p.m. to 2 a.m. This prompted the faculty in April 1919 to declare that Davidson was an “instrument of the Presbyterian Church” and “subject to the rules and regulations of the Church Court.” College organizations like the St. Cecelia Club, “whose avowed purpose [was] to promote dancing” were forbidden, and the club was disbanded for “flagrant violation” of college rules which “brought discredit upon the College in the eyes of its constituency.”

This was certainly true of Concord Presbytery, the founding presbytery of the College, which in September 1919 condemned the “dances of today as a moral and spiritual evil,” which encouraged “physical intimacy.” Particularly damaging were dances in which “the arms of the dancers partly or wholly encircle persons of the opposite sex.” This put the College in a difficult position, since they could hardly hope to control dances held off-campus in Charlotte. It was also difficult for the college to maintain, as World War I had resulted in a change in social life in the country as a whole, with dancing, drinking, and gambling becoming more accepted. The advent of Prohibition in 1920, however, somewhat reduced the danger of drinking at these events.

In the years that followed, there continued to be dancing in Charlotte during the opening of school, commencement, at Thanksgiving, and at the time of the junior speaking. With the demise of the St. Cecelia Club, dances were held by fraternities and individual classes. One such dance, held during commencement in 1921, was described by the Charlotte News and Evening Chronicle as “one of the most delightful dances of the season.” It was attended by hundreds of Davidson students and alumni, and “Hosts of North Carolina’s most attractive girls…beautifully gowned.” The scene was “one of exceptional beauty,” and the hall was “profusely decorated…At midnight, the grand march took place, and paper caps, serpentine streamers and confetti were distributed to all the dancers.”

In November of the following year, college president William J. Martin wrote a letter to the Charlotte Observer, later reprinted in the Washington Progress, criticizing the use of the College’s name in advertising dances, and “requesting that the placards that have been printed and distributed in Charlotte advertising a ‘Carolina-Davidson’ dance at the city auditorium Saturday night be removed and destroyed.” He went on to say that he did not know “who the parties responsible are, but I wish to say, and to say it emphatically, that no-one is authorized to use the name of Davidson college in such connection…Davidson college is owned and controlled by the Presbyterian church and…in my official capacity as president of the college, I am a servant of that church, whose stand on the dance is pretty generally understood.” Local newspapers continued to comment on dances, however, which continued unchecked.

Walter L. Lingle was named president of the college in 1929, and as he states in his memoirs, “The perennial dance problem bobbed up soon after I arrived and like Banquo’s ghost would not down.” According to Lingle, in 1930 the trustees, avoiding the word “dance,” (which by then even the Davidsonian could not use) asked the president and faculty to pay attention to “the importance of protecting the good name of the college in…social gatherings.”

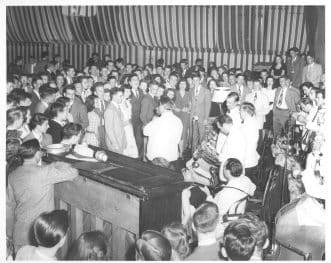

Davidson students at a dance in 1947 (photo courtesy of the Davidson College Archives)

Despite Prohibition, rumors had been circulating about drinking and other misbehavior at the dances, and it was feared that the college’s reputation would be damaged. The following year a group of students sent a petition to the trustees requesting that dances be allowed on campus. The various presbyteries supporting the college protested, and the request was denied. According to Lingle, the reason given was that the board didn’t want to be “out of harmony with the deliverances of the highest Court of our Church, or in opposition to the wishes of the controlling presbyteries.”

On April 23 the Elkin Tribune opined that “The question of whether dancing should be allowed at Davidson College has used up much valuable space in the newspapers recently, and with the result that the youngsters will probably use their own judgment about the matter and either find a way or make one — to dance.”

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, once again raising the specter of student drinking. Off-campus dances continued, and in 1935 the students asked the trustees once again to have dances on campus. This, too, was denied. The trustees did appoint a committee to ask the various presbyteries their opinions on the issue. Shelby’s Cleveland Star reported on April 19 that King’s Mountain Presbytery, after “a spirited and lengthy discussion,” voiced its disapproval; Winston-Salem Presbytery concurred. Students repeated their request again in February 1936 and were, again, denied.

That same year the Board of Trustees resolved that they would receive no more petitions directly from the students, and that such petitions would have to be presented to the faculty. who would then send a recommendation on to the board. Still unable to hold dances on campus, the students continued to hold them in Charlotte with faculty approval. In late 1937, Dean Mark Sentelle attempted to limit drinking at these off-campus events. According to the December 2 edition of Mooresville’s Rounder and News-Leader, Sentelle had recently presented the students with a choice: either have dances with no liquor or not have dances at all. In response the students voted overwhelmingly to create a control committee of 21 members “designated to see to it that all Davidson dances are free from liquor.”

Members would have authority during the twelve hours preceding and the twelve hours following each dance and were “empowered to report directly to the faculty all liquor drinkers at the dances or those carrying liquor there.” There is no information on how this worked out.

Mores began to change with the outbreak of World War II. During that time soldiers enrolled in military training at the college were allowed to hold dances on campus. Students were excluded from these affairs but finally, in 1944, the faculty decided to “permit dances on campus “ at such times and under such conditions as may be determined by the faculty. It seems like a bow to the inevitable, as soldiers returning to the college after the war were older, sometimes married, and familiar with customs elsewhere.

On February 9, 1945, more than a century after the college was founded, the first campus dance occurred in the Alumni Gymnasium. It is remarkable that the college and the church that founded it were able to hang on to their convictions through all the social upheaval of the early twentieth century.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.