NEWS

Forgotten History II: Plantations near Davidson

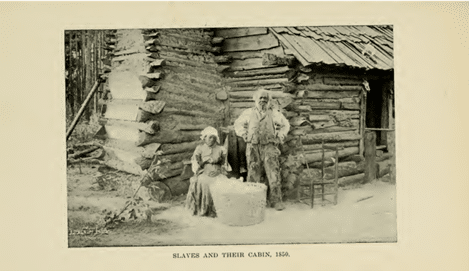

(Photo from Alexander McKelway’s History of Mecklenburg County)

The local slave population was much larger when one considers the numerous large plantations around Davidson, situated in both Mecklenburg and Iredell counties. Slaveowners had settled the region during the 18th century, and when Eli Whitney’s cotton gin came into general use around 1800, the production of cotton became much easier. Consequently, cotton acreage increased along with the numbers of enslaved people needed to cultivate them. In his book The Plantation World Around Davidson, Chalmers Davidson notes that by 1850, in Mecklenburg County alone, there were 17 planters who owned 30 or more slaves each.

The local slave population was much larger when one considers the numerous large plantations around Davidson, situated in both Mecklenburg and Iredell counties. Slaveowners had settled the region during the 18th century, and when Eli Whitney’s cotton gin came into general use around 1800, the production of cotton became much easier. Consequently, cotton acreage increased along with the numbers of enslaved people needed to cultivate them. In his book The Plantation World Around Davidson, Chalmers Davidson notes that by 1850, in Mecklenburg County alone, there were 17 planters who owned 30 or more slaves each.

By 1860, this number had increased to 30. The earliest plantation owners built log homes, which were later clapboarded or replaced with frame or, occasionally, brick dwellings. Slaves lived in small log cabins, housing between three and five people. While a few slaves may have been trained as blacksmiths or carpenters, the majority of them either worked in the cotton fields or in the plantation house.

(The above photo comes from Alexander McKelway’s History of Mecklenburg County)

There were three plantations in or near the village of Davidson College: Walnut Grove (owned by James Johnston), the W.G. Potts plantation, and Beaver Dam, home of William Lee Davidson II. Only Beaver Dam still stands. One of the earliest slaveowners in Mecklenburg County was James Johnston’s father, Patrick Johnston, who came to North Carolina from Ireland in 1787. When he arrived, he engaged in the weaving trade. He married Annie Wall in 1794, and in 1810 they were living with the family of Captain B. Willson.

By 1820 they had their own home, with two members of the family engaged in agriculture, and two in manufacturing. By this time there were seven children, and the plantation had 30 enslaved people. By 1840, there were only four white people living in the household and 24 slaves. Patrick Johnston died in November 1844, and his will gives an indication of the amount of land and the number of slaves he had.

In his will, he gave his wife Anna the plantation where he lived along with “six negroes of her choice, subject to her disposal.” Anna Johnston, however, had predeceased James, dying in 1843. To his daughter Rachel Houston, wife of George Sidney Houston, a plantation owner in Mount Mourne, he gave the “the plantations known as the Rodgers and Littles places” as well as the enslaved people, Rose, Ait, Anthony, and Dick. To his son James he gave “the plantation he currently lived on” (Walnut Grove) “as well as the Maxwell place and a number of slaves. He gave his son Houston “the Cathey plantation and the plantation on which I reside at his mother’s death,” along with the enslaved people, Jack, Ellick, Bryson, Toney, and Prince.

His daughter Mary Lowrie (she married Samuel Lowrie in 1830; he died in 1846) received “the plantation known as the Henry or Wright place, and the Graham place,” as well as the slaves, Pine, Tilla, Sill, and Harry. A codicil to his will gave Mary another plantation instead, and it stated that the Henry or Wright place be sold and the proceeds divided among the heirs. To his grandchildren he gave either land or money. He only conveyed one slave, Sam, to his grandson Patrick Lowrie. One of Patrick’s other sons, Robert, was also a wealthy plantation owner. His plantation, called Cedar Grove, was located on Beattie’s Ford Road, and in 1860 he owned 32 slaves.

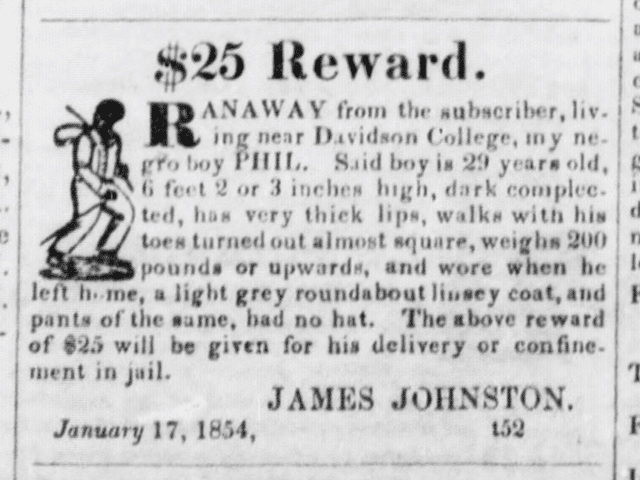

Patrick’s oldest son James was born in 1801, and he married Anna Bona Torrence in 1824. Anna was the daughter of another slaveowner, Alexander Torrence of Iredell County. James Johnston’s plantation house, Walnut Grove, was located on the present South Main Street, near where Whit’s Frozen Custard is today. He had a large property with many outbuildings, and he was one of the largest slaveowners in Mecklenburg County, owning 40 slaves in 1850 and 48 by 1860. According to a descendent, “To his many slaves…he was a considerate master. He was generous and kind but very strict.” In January 1854, one of his slaves ran away, and he posted a notice in the newspaper offering a $25 reward for his “negro boy” Phil, who at the time was “29 years old, 6 feet 2 or 3 inches high, dark complected” with “very thick lips.” It is interesting that Phil, although he was 29 years old, was still referred to as “boy.”

James Johnston died in 1860 at the age of 59. His will gave a quantity of information about his personal property, including his slaves. His executors, Samuel M. Withers, W.D. Withers, and William G. Potts sold his household goods, farm implements, livestock, and other possessions at a public auction in November of 1860 for $7385.19. An earlier inventory of his property, compiled by his executors in March of that year, includes a list of the plantation’s enslaved people. Among these were eight adult women, ranging in age from 20 to 60. Of these, several had a number of children: Mary, age 40, nine children; Harriet, age 38, 12 children; Margaret, age 32, eight children; Jane, age 36, two children, Mary, age 22, one child; and Sarah, age 20, one child.

The other women slaves were Sukey (60 years old) and Rose (50 years old). There were 11 female children included. Their names and ages were as follows: Silvy (17), Martha (16), Caroline (17), Ann (15), Big Esther (14), Little Esther (13), Julia (8), Jane (5), Nannie (3), Sarah Ann (3), and Blanch (18 months). The estate also included 13 enslaved men: Ben (30), Wilborn (30), William (20), Plumb (40), Rance (30), Milus (20), Monroe (20), Fayette (20), Stephen (20), John (19), Wade (17), George (18), and Peter (19).

Phil’s name did not appear. All of these men were fairly young and presumably strong and able. Johnston apparently also had a half share in Elijah, age 40, who was a bootmaker. There were 12 young, enslaved boys listed in the inventory: William (8), Thomas (5), Thomas (2), Claud (11), Francis (10), Ed (8), James (5), Alex (4), Guy (10), Andy (8), John (1) and an illegible name (1). Note that Silvy and Caroline, both 17, were considered girls, while Wade, who was the same age, was considered a man. There is no information available on the disposition of Johnston’s slaves.

The family of William Graham Potts had also been in North Carolina since the 18th century. His grandfather, James Potts, settled in what is now Iredell County sometime after 1750. William was born in May of 1818 and married Rebecca Torrence, another daughter of Alexander Torrence, in 1839. According to Chalmers Davidson, Potts had built his house, located near the former Hoke Lumber Company in Davidson, by at least 1845. In 1850 he owned 40 slaves, and by 1860 he had 50. However, the plantation in Davidson was not his home plantation, as at some point he moved to the Lowrie plantation (mentioned above) on Beatties Ford Road. When he died in 1865, he was renting out his tract of land in Davidson.

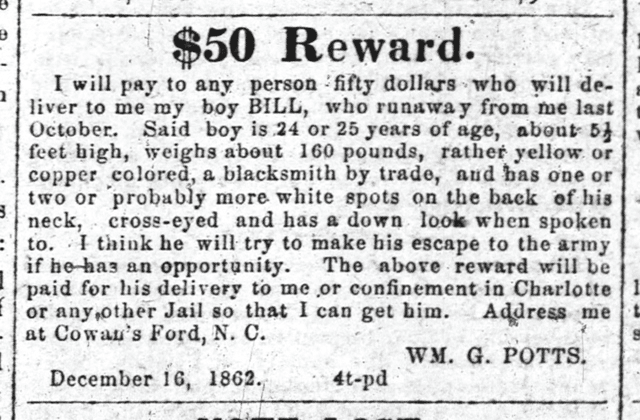

Little is known about Potts’ slaves, because he died in 1865, after Emancipation. He did, however, advertise for a runaway slave in December 1862. He offered $50 dollars for “my boy Bill” who had run away in October. Bill, aged 24 or 25, was “about 5 ½ feet high, weighs about 160 pounds, rather yellow or copper colored, a blacksmith by trade…cross-eyed and has a down look when spoken to.” Potts speculated that Bill would try to join the Union Army if he had the opportunity.

Just outside Davidson was Beaver Dam, the plantation of William Lee Davidson. By 1830, he owned 25 slaves. An account of life at Beaver Dam, written by Stonewall Jackson’s wife, remarked on Davidson’s first wife, Betsy. According to Mary Anna Jackson, “Her love for me seemed to communicate itself to the slave women of her household, and Aunt Rose, and Aunt Phoebe, Ruth and Rachel, Letty and Katty seemed to vie with each other in trying to make me happy. The Davidson family moved to Alabama and Davidson sold his land on Beaver Dam Creek to Joseph Patterson, another successful planter. Presumably he took his enslaved people with him.

The 1850 census lists Davidson in Marengo County, Alabama, where he owned property worth $8540, along with 38 slaves. He left his wife, Sarah Davidson, the slaves named Jim, Linda, Elenor, Aaron and his wife Martha and her child Jim “and such children as she may hereafter have.” Sarah also received Metz, Yellow Sarah, Black Harriet along with her child Horace and her husband John. She was also to take possession of Phebe, Rose, and Amy (mentioned above in Mrs. Jackson’s account), “and support and maintain them so long as they live.”

He also instructed his executors to sell the remaining slaves “so far as practical in families so that mother and small children be kept together as much as can be conveniently done.” They were to be sold publicly or privately “after having them fairly appraised and valued by competent & disinterested persons.”

There were many other plantations in Iredell County, some only a mile or two from the village of Davidson College. As you can see above, many of the owners of these plantations were associated by birth or marriage with their counterparts in Mecklenburg County. These nearby plantations will be discussed in the next installment.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.