NEWS

Echoes of Slavery: The Johnsons

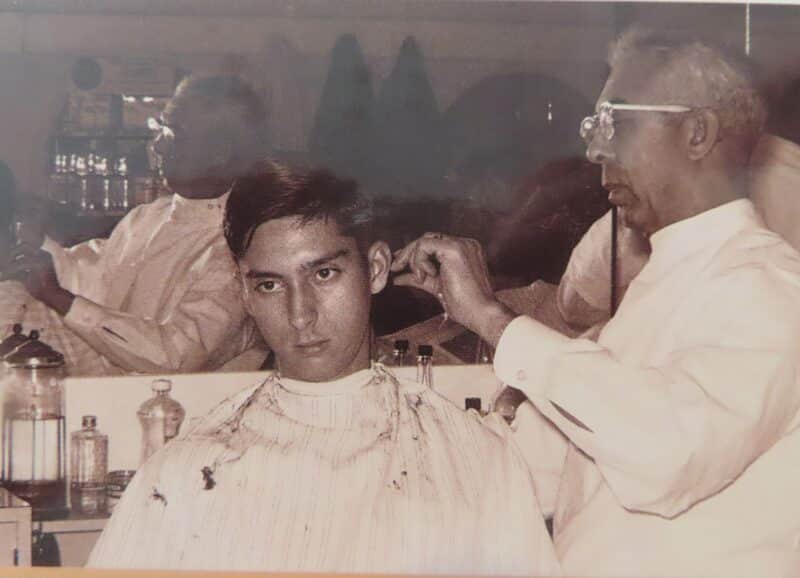

Ralph Johnson from nis book, “And David Played his Harp”

While slavery in the United States ended over 150 years ago, echoes still exist around Davidson today. Clues lie all around us: in books like Ralph Johnson’s David Played a Harp, in monuments in the Christian Aid Society Cemetery and other Black cemeteries, in letters and diaries. Names of the major slave owners have passed down through generations of their formerly enslaved people and are well known to us today.

While slavery in the United States ended over 150 years ago, echoes still exist around Davidson today. Clues lie all around us: in books like Ralph Johnson’s David Played a Harp, in monuments in the Christian Aid Society Cemetery and other Black cemeteries, in letters and diaries. Names of the major slave owners have passed down through generations of their formerly enslaved people and are well known to us today.

One of these, late Davidson barber Ralph Johnson, was descended from slaves on both sides of his family. Although he used the surname Johnson, the family name of several of his ancestors was given as both Johnston and Johnson in early census records. In addition, there were other Johnson (Johnston) slave descendants who settled in Davidson. Several of these seem to have descended from slaves owned by James Johnston at Walnut Grove. Since slave records are either non-existent or difficult to interpret, the following has been pieced together from reminiscences and census records.

Ralph Johnson’s great-grandparents were slaves Elijah (Lige) and Dilsey Johnson. The ownership of Elijah Johnson, like that of many slaves, is uncertain. Ralph Johnson was told that Lige went to Virginia to retrieve the body of his master after he was killed at Spottsylvania during the Civil War. James Johnston had no sons who fought in the war. His brother, Robert Houston Johnston of Cedar Grove, had a son named Barnabas who was killed there, but there are no records showing that Robert or Barnabas owned a slave named Elijah. An 1860 inventory of James Johnston’s estate, however, shows that he had a half share in a slave named Elijah, age 20, who was a bootmaker. It may be that James and his brother shared ownership in Elijah.

In 1870 Elijah, who was born around 1824, was living in Lemley Township with his wife Dilsey, born around 1840. They were living in the home of a prosperous white widow, Rebecca Johnson. Elijah, who was illiterate, worked as a farm laborer. The fact that slaves were not educated limited their futures after the war, a situation which sometimes existed for generations because of the lack of, or inferiority of, education for African Americans.

Elijah and Dilsey were still in Lemley Township in 1880, but this time they had their own household. Both Elijah and Dilsey were farm laborers, and both were still illiterate. Also in the household were Elijah’s mother, Amie Potts, Elijah and Dilsey’s son William, who was four years old, and their grandson, eleven-month-old Walter. Public records indicate that Walter was the son of their daughter Alice Johnston. In his book David Played a Harp, Ralph Johnson reports that Dilsey Johnston was still alive when he was a young man, living with her son William. He also indicates that Alice’s child, his father Walter, was fathered by the son of a prominent doctor in whose home she worked for a time. According to Ralph Johnson, Alice never spoke about this.

In 1900, Alice married Richard Robinson, and by the time of the census that year, Dilsey Johnston, sixty-five and a widow, was living with them in Deweese Township. Alice’s brother Tobias, aged 16, was also living there. The census records indicate that Dilsey had fourteen children, four of whom were still living. Three of these were Alice, Tobias, and Will. Alice eventually had four children, Walter, Jenny, Odell, and Charlotte. She gave the children the last name Johnson, as she had been impregnated by a man of that name. In 1910, Alice was working as a laundress and living in Deweese Township. By 1920, she was living on Mock’s Hill and was widowed. She was still working as a laundress. Alice died in August 1931.

Ralph Johnson remembers his grandmother Alice as “a heavy-set, chocolate-colored woman,” and a “very kind person.” With the exception of Walter, who was light skinned, all of her children had darker complexions. Jenny eventually married Ernest Byers, the son of Andy Byers. Charlotte married Charlie Wilson, a longtime employee of the Davidson College athletic department. He was nicknamed “Doc Charlie” because he was able to treat the athletes’ minor sprains and injuries.

Alice’s two brothers, Will Lige and Otho (Tobe) Johnson, were also well known in the Davidson community. Will owned Davidson’s only freight wagon, and he hauled goods from the depot to all the merchants in town. He was also instrumental in founding the Christian Aid Society, originally organized to pay its members’ medical and burial expenses. This later led to the establishment of the Christian Aid Society cemetery near the Davidson College campus, where many of these former slaves are buried. Tobe Johnson owned the only cleaning and pressing establishment in Davidson, which also provided alterations. According to Ralph Johnson, “everybody knew him and patronized his place of business.” He was a kindhearted man, and Ralph’s favorite uncle.

Walter Johnson, Ralph Johnson’s father and Alice’s son, was born in 1879. In 1900 he was living with his mother Alice and stepfather, Richard Robinson, and working as a barber. In 1903, he married Bessie Norton, who was also descended from slaves. By 1910, Walter and Bessie owned their own home, and Walter was running his own barber shop. He could both read and write. Living with them was their son Ralph, who was five. Walter died in 1912, at the age of 34, and his death certificate lists Alice Robinson as his mother and his father as unknown. By the time of his death, he and Bessie had an additional child, a daughter named Erving. In his book, David Played a Harp, Ralph describes the struggles of the young widow to try to keep the barber business running and her family housed and fed.

Two other former enslaved people from James Johnston’s Walnut Grove may have settled near Davidson. The first was Plum Johnston, who is listed as “Plumb” in an 1860 inventory of James Johnston’s estate. At the time he was around 40 years old. Also listed in the will were 36-year-old Jane and her two children. In 1870, Plum and Jane Johnston were living in Deweese Township. Both were illiterate, and Plum was working as a farm laborer. They owned no real or personal property. Living with them was their son, Peter Johnston, born around 1842. A young man named Peter, born around 1841, was also listed in the 1860 inventory of James Johnston’s slaves. Peter was also working on a farm and could read but not write. Also in the household were Hannah Lowry (58), Martha Lowry (30), and three Lowry children: James (5), Edward (4), and Sallie (1 month). There may have been a connection between the Johnston and Lowry (Lowrie) families, as James Johnston’s sister Mary married Samuel Lowrie in 1849. There is no information available on Plum Johnston and his family after 1870.

Another of James Johnston’s slaves, Ransom (Rance) also remained in Davidson after the Civil War. Ransom, born around 1830, was listed in the 1860 inventory of James Johnston’s estate. In 1870 he was living near Davidson and working as a blacksmith. Like most former slaves, he was illiterate, but unlike some he had personal property of $400. Also in the family were his wife Mary and their children Wood (10), Cloyd (9), Rose (8), Nancy (7), Lemly (6) and Bonnie (4 months). All were illiterate, and none were attending school. Rose Johnston, age 56, was also living with them; an enslaved woman of that age named Rose was also listed in the 1860 slave inventory. According to a later death certificate filed for Ransom and Mary’s daughter, Rose, in 1915, Mary’s maiden name was Byers, and she was born in Iredell County. She may have been enslaved by the Byers family there.

By 1880, Ransom Johnston was a farmer in Providence Township in Mecklenburg County. Mary may have died, because on December 5, 1878, he married Margaret Miller. In 1880, Cloyd (Claude), Rose (Rosanna) and Lemley were living with them along with several of Margaret’s children. Everyone in the family was illiterate, and all the children from age 11 up were working on the farm. None were attending school. There is no reliable information available on Ransom Johnston after 1880.

Even this discussion of a single family serves to illustrate the difficulties formerly enslaved people endured following their sudden liberation. As freedmen, they had no education, no property, and very few employment options. Ralph Johnson’s father Walter, son of a former slave, trained as a barber and was able to have a business and eventually own a home, but others, even if they had been trained as blacksmiths or bootmakers, were forced to fall back on tenant farming. Ralph Johnson was educated, although in a piecemeal fashion, but few other children were. With the 19th century Jim Crow laws and the lack of quality education for Blacks in the South, these disadvantages would continue far into the 20th century.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.