NEWS

Tobe’s Pressing Club

The process that we now refer to as “dry cleaning” has developed over many centuries. As far back as the Roman Empire, professional cleaners used lye and ammonia, combined with a kind of clay called fuller’s earth, to absorb dirt and grease from garments that could not be laundered. Centuries later, around 1700, cleaners began using the solvent turpentine to treat fat and oil stains. This method was reportedly discovered when a cleaner accidentally spilled turpentine on a greasy fabric, dissolving the grease.

The process that we now refer to as “dry cleaning” has developed over many centuries. As far back as the Roman Empire, professional cleaners used lye and ammonia, combined with a kind of clay called fuller’s earth, to absorb dirt and grease from garments that could not be laundered. Centuries later, around 1700, cleaners began using the solvent turpentine to treat fat and oil stains. This method was reportedly discovered when a cleaner accidentally spilled turpentine on a greasy fabric, dissolving the grease.

In the United States Thomas L. Jennings introduced solvent-based cleaning in 1821, calling the method “dry scouring.” Twenty-four years later, Parisian Jean Baptiste Jolly developed a cleaning method that used kerosene and gasoline and opened the first dry cleaners in Paris.

Early dry cleaning was frequently done by women, white and black, in their homes. From caring for their own clothes, they began to take in stained clothing from local residents. In a 1900 Good Housekeeping article entitled “New Sources of Income,” Isabel Gordon Curtis reports that “In everyday life everywhere one hears of women who have built up for themselves a business which means a comfortable living earned under the home roof. One instance which occurs to me is that of a young woman whose story was the familiar one of being suddenly thrown on her own resources. She had no talent of any sort; she could not sew or cook and the future looked ominous. She thought of her only capability, that of keeping her clothes in good order. She could make a grease spot vanish as if by magic, and she could use a hot iron on a cloth suit as ably as any tailor.”

Dry cleaning soon became more popular, and those who could afford it began joining “pressing clubs.” At first services were supplied in the home, but soon most such businesses moved into small stores. To belong to the “club,” patrons paid a small fee, sometimes $1 per month or $10 per year. This might allow them to have their clothes cleaned and pressed twice a month. Such shops also offered alterations and garment repair.

Many African American men established such shops; while they were not as numerous as Black barbers, they were well-represented among shop owners. There were many examples of Black proprietors in North Carolina, including Simpson Dogan’s dyeing and cleaning shop in Hendersonville, founded before 1902, and the shop of his competitors, Rosa and James Pilgrim, founded in the 1910s and called the 5th Avenue (West) Pressing Club. Winston Salem had its own Black dry cleaners, the Busy Bee Pressing Club, which was founded in 1922.

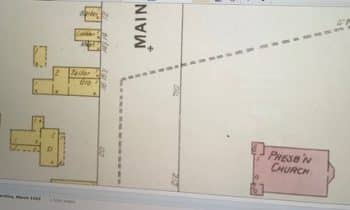

Sanborn map of North Main Street, Davidson, 1902. The three small wooden buildings are shown on the upper left.

Davidson had its own pressing club, established by African American Otho “Tobe” Johnson, who was barber Ralph Johnson’s uncle. The shop opened on North Main Street sometime before 1910. He charged 25 cents to sponge and press a man’s suit. When Ralph Johnson’s father, barber Walter Johnson, died in 1912, Ralph began working for Tobe after school and on weekends to help support his mother and sister. The shop was located in one of several one-story wooden buildings on Main Street.

In his memoir David Played a Harp, Ralph Johnson described the shop as follows: “On each side of the narrow double doors at the entrance, there was a single window with ordinary small windowpanes. Five wooden steps led up from the cement sidewalk to the doors. On the inside a small lobby was formed by a wall about four feet high in the center front. At one side of the lobby wall and in front of the window there was a long wide table…where the clothes were sponged and pressed. The alteration and repair department was on the opposite side. Uncle Tobe’s sewing machine sat at that window. At the back of the wall clothes that had been finished were put on hangers and hung on long pipes extended across the room.”

The pressing table was covered with layers of duck cloth, a type of canvas, and held two shallow washing pans. To sponge a garment, a brush was dipped

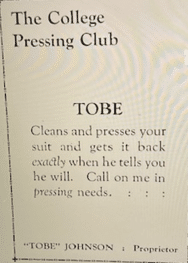

Ad from Davidson yearbook “Quips and Cranks,” 1918

into one of these pans, which contained gasoline, and brushed over the item. To press it, the garment was spread out, cloth was laid over the part to be pressed, and clean water was sprinkled over it from the second pan. It was then pressed with an electric iron. In later years, Tobe purchased a steam pressing machine with a gasoline boiler to provide steam; by 1924 he had added a machine to dry clean the clothes.

In 1921, Ralph opened his first barber shop next door to the pressing club, and in 1922 both shops moved farther down Main Street when the wooden buildings were demolished for new construction. Tobe’s shop was frequented not only by local residents, but by many college students. He advertised in college publications, and one student, Alexander Mitchell, even included “Member Tobe Pressing Club” in his senior writeup in Quips and Cranks in 1921.

Because the various solvents used in dry cleaning were dangerously flammable, in 1921 the state of North Carolina began to tax pressing clubs. Those which employed only two people were charged $5 a year, and those with more employees were charged $10. By 1924, the year Tobe Johnson died at the age of 44, a dry cleaner from Atlanta had developed the Stoddard solvent, which was slightly less flammable.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.