NEWS

To Design Cities Right, We Need to Focus on People

Tim Keane

(Tim Keane was Davidson’s first fulltime planning director, coming to town in the mid-90’s. He expertly guided us to a new way of thinking about planning that took into consideration the people who would use and occupy the spaces, both old and new, that we would build and inhabit. Tim went on to be planning director for Charleston, Atlanta, Boise, and in April, he will move to Calgary, Canada to be that lucky city’s General Manager of Planning and Development Services. The Editors of News of Davidson requested that Tim allow us to reprint the following article from Scientific American, February 15. He graciously agreed. Many thanks, Tim.)

Far too often, city planning is approached as an engineering problem, instead of connecting people with the land.

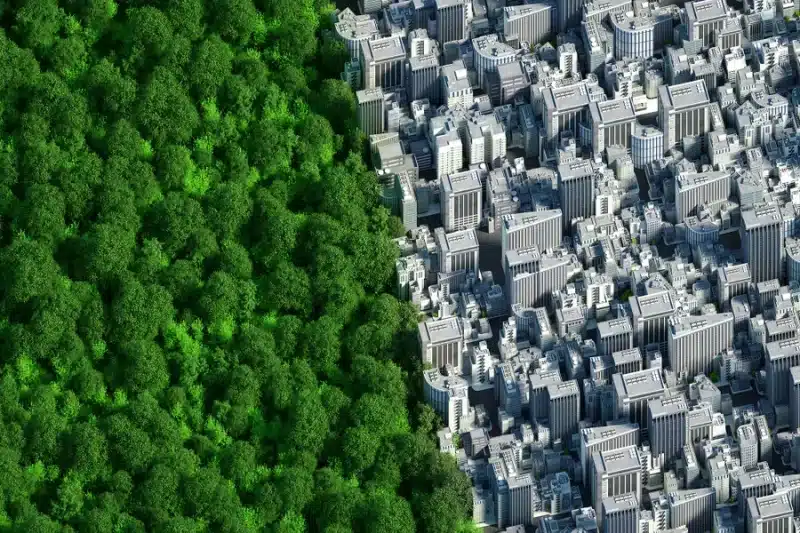

Digital generated image of two semi spheres connected together in one planet. Left part covered by trees against right part fully urban and covered by buildings. Credit: Andriy Onufriyenko/Getty Images

In the mid-1990s, soon after I was hired by the town of Davidson, N.C., as its first full-time town planner, I attended a joint public meeting in the neighboring town of Cornelius. Davidson was at odds with the county’s proposed thoroughfare plan. The plan reflected the type of misguided investment that communities have been making for decades, furthering sprawl under the guise of development. Davidson city officials hired me because its people foresaw that a proliferation of subdivisions and shopping centers would irrevocably alter the dynamics of this old, distinctive college town and its countryside.

When I arrived in the dark-paneled, musty Cornelius Town Hall, a resident was berating the Cornelius planner, demanding to be told who had drawn the lines on the thoroughfare plan map. The lines represented future “major” and “minor” roads, and people knew instinctively what they signified: highways clogged with cars, surrounded by parking lots, stale buildings, sad berms and endless subdivisions.

I intervened and informed the resident that I had drawn the lines (although I hadn’t), and what about it? I explained that he and everyone else in the room were the reason for those lines. They had come to live in the countryside, and they had made the choice to drive everywhere in order to do anything. Suddenly, the meeting became productive, focused on what we were creating collectively, rather than what “the government” was inflicting upon them.

Our work in the U.S. to make better neighborhoods, towns and cities is a hapless and obdurate mess. If you’ve attended a planning meeting anywhere, you have probably witnessed the miserable process in action—unrestrainedly selfish fighting about false choices and seemingly inane procedures. Rather than designing places for people, we see cities as a collection of mechanical problems with technical and legal solutions. We distract ourselves with the latest rebranded ideas about places—smart growth, resilient cities, complete streets, just cities, 15-minute cities, happy cities—rather than getting down to the actual work of designing the physical place. This lacks a fundamental vision. And it’s not succeeding.

Our flawed approach to city planning started a century ago. The first modern city plan was produced for Cincinnati in 1925 by the Technical Advisory Corporation, founded in 1913 by George Burdett Ford and E.P. Goodrich in New York City. New York adopted the country’s first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1916, an effort Ford led. Not coincidentally, the advent of zoning, and then comprehensive planning, corresponded directly with the great migration of six million Black people from the South to Northern, Midwestern and Western cities. New city planning practices were a technical means to discriminate and exclude.

This first comprehensive plan also ushered in another type of dehumanization: city planning by formula. To justify widening downtown streets by cutting into sidewalks, engineers used a calculation that reflected the cost to operate an automobile in a congested area—including the cost of a human life, because crashes killed people. Engineers also calculated the value of a sidewalk through a formula based on how many people the elevators in adjoining buildings could deliver at peak times. In the end, Cincinnati’s planners recommended widening the streets for cars, which were becoming more common, by shrinking sidewalks. City planning became an engineering equation, and one focused on separating people and spreading the city out to the maximum extent possible.

We still use similar techniques today, planning cities project by project, “balancing” individual property rights and interests and concentrating on administrative processes. We argue for months or years about each project and are never satisfied. What distinguishes city planning from other pursuits is its concentration on the whole community. We have become dreadful at this. Moving from project to project, or zoning case to zoning case, is not what differentiates planning; the administrators and lawyers can handle that. Exceptional solutions to our biggest city planning problems, such as housing affordability and climate resilience, will never be achieved piecemeal.

Planning should be chiefly a design process, not a legal one. Design-based, community-scaled solutions are paramount because we now must grow within our existing places rather than sprawl, which has ruined too much land, generated too many greenhouse gas emissions and wasted too much time as we drive for every simple thing. The city and all its neighborhoods must get better with more people in them.

We need to design physical cities to be more enriching and distinguished. The degree to which a city becomes more equitable and resilient has to do with its physical attributes. How the physical city changes determines the degree to which we can deal with housing affordability, mobility and climate adaptation.

Making places that are resilient and economically, socially and environmentally sustainable requires a different relationship with the land. Creating the incredible amount and diversity of housing we desperately need is possible only when we examine how to design and build in existing neighborhoods and on existing streets. The best solution to building on the vacant lot down the street will not be found in land-use law and litigation.

The best buildings have an overarching design concept that leads design of the details. If we are to address our greatest problems, the same principle—an overarching design concept—must apply to cities also.

Boise, Idaho, where I am currently city planner, is an interesting example. The built urban and suburban parts of this midsized city are in close relationship with the nature that surrounds the city—the desert to the south and foothills to the north. Boise can grow entirely within its existing footprint.

The city took a significant step in this direction in 2023 by enacting a new set of citywide rules based upon the physical attributes we seek: a denser city with a great diversity of housing, making walking and transit real options for more people; a city that grows in a way that intrinsically depletes less of our natural resources like water and energy. Boise’s discussions and decision are conceived at the scale of the city, including unlocking the ingenuity of the entire community.

A version of this approach can exist for every city, no matter its size. I’ve explored these issues in a small town, small city and big city: first Davidson, then Charleston, S.C., then Atlanta—and now Boise. As Atlanta’s guiding document, the Atlanta City Design, says: “When we talk about design, we’re not merely describing the logical assembly of people, things and places. We’re talking about intentionally shaping the way we live our lives.” This is achieved through a thorough understanding of the place and how its physical attributes can best enable creativity, ingenuity and restoration.

It is significant that the angry man at the county meeting in North Carolina was pointing to a place on the map that was for centuries traversed by the trails of what is known as the Occaneechi Path. This route, which connected communities of Indigenous peoples, was eventually overlaid, first by the railroad and then the interstate, each built atop the disease, violence and death wrought by European settlers, with the builders sowing new devastation and division of their own.

Hope and action lie not in furthering our most destructive national obsession of consuming more land and greater resources, compounded by procedural and administrative waste. Only by committing ourselves to acknowledge, atone, repair and restore, as we design cities as physical space, is there any chance for being in relation with each other, with nature and with the land.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.