NEWS

The Dave McLean Community Center: by Nancy Griffith for Black History Month

The Ada Jenkins Center as we know it today was preceded by an earlier community center sponsored by the Davidson College YMCA and the Women’s Civic League. In 1938, the college Y organized a Committee on Colored Work, headed by student Dave McLean. At the time, they were already providing a night school, a Boy Scout troop, and high school football and volleyball programs, all held at the Davidson Colored School (later renamed the Ada Jenkins School). The school, however, was not large enough to accommodate all of these activities, so the West Side community and the Y decided to collaborate on a community center.

The Ada Jenkins Center as we know it today was preceded by an earlier community center sponsored by the Davidson College YMCA and the Women’s Civic League. In 1938, the college Y organized a Committee on Colored Work, headed by student Dave McLean. At the time, they were already providing a night school, a Boy Scout troop, and high school football and volleyball programs, all held at the Davidson Colored School (later renamed the Ada Jenkins School). The school, however, was not large enough to accommodate all of these activities, so the West Side community and the Y decided to collaborate on a community center.

In December of 1939, the Y designated the community center as the recipient of its proposed $800 Christmas gift fund. In addition to providing a building on the school grounds where groups from the community could meet, they hoped to clear two fields nearby for football, basketball, and baseball. The Civic League also planned to use the facility for sewing and cooking classes. The planned building was to measure twenty by thirty feet and would include a meeting room and a kitchen. The Civic League promised to provide the furniture, and the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) was enlisted to grade the playground.

By early April of 1940, construction, planned by the Y, the League, and several members of the college faculty, was underway. The Black community was actively involved in the project, helping with construction and raising money to support it. By late May, the new community center, which would bear Dave McLean’s name, had been completed. Although McLean graduated that spring, the work of the center would continue for a number of years.

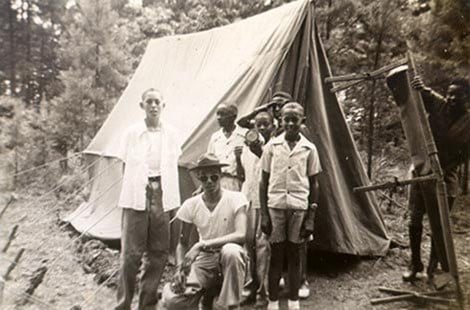

Ken Norton and Troop 75, taken circa 1940 (Courtesy of the Davidson College Archives)

By October, there was an adult school at the center, and the Y had applied to the WPA for two recreational workers to help with programming. Plans were derailed when an electrical fire damaged the building in mid-November, but by the end of January, repairs had been completed, and two young Black WPA workers were hired to help with the work. There were efforts to organize a Girl Scout troop, and proposed classes included nature study and singing. Since so many mothers in the community worked, the Civic League was hoping to establish a preschool, as well as an employment agency to help younger men find jobs. In February 1941, Y members began to hold discussions of various social problems and hoped to organize an open forum with white youth to discuss problems facing both races. Mr. Poe, the principal, supported this effort, but the principal of the white school demurred, and the forum was never held.

By May of 1942, the government had withdrawn funding for one of the WPA workers. Mr. Poe tried to compensate by keeping the hut open two nights a week but couldn’t find a suitable person to take over for him while he was attending summer school. By the following November, one of the WPA workers was back at work, keeping the hut open two or three evenings a week. For the next several years, there were a number of issues with operating the center’s programs. In 1946, the Y decided to revitalize the community center, but was delayed by “distracting developments.”

Before anything was done, the African American community wanted to investigate what was needed and how best to provide it. By mid-October, the Civic League was the trustee of the property, and there was a control council that included five African Americans, among them Ralph Johnson and Kenneth Norton. The council also worked closely with Mr. Poe and Reverend Wells of the Unity Church (formerly the Mill Chapel). Plans were to have the center open daily from 3 until 5 p.m. The League appropriated $150 for equipment, a coal bin, a nursery and a weekly movie.

This effort was successful, but the school decided to use the building as a lunchroom, and The Davidsonian reported that the tables necessary for the lunchroom left almost no room for indoor activities. While the school property consisted of four acres, it was “so chopped up, ungraded and uneven that hardly more than an acre is really fit for use.” Despite these limitations, the program was providing boxing, ping pong, darts, softball, basketball, and football. This effort was so successful that they kept it open on weekday afternoons during the summer.

An article published in The Davidsonian in November 1948 described the governing structure for the community center. Since the YMCA leadership was always changing, the Civic League managed “all the legal documents and also [served] as a permanent advisory board.” The “Colored Board of Control,” which included new school principal J.O. Harris, one person from each of the three African American churches, a member of the Christian Aid and Benevolent Society, and a teacher from the school, acted as the “chief director.” At the same time, the Civic League was deciding whether to continue their financial support of the community center in hopes that residents of the West Side would take over.

Despite these concerns about continuing to fund the community center, the Civic League did maintain a relationship with the program. In January 1949, they voted to help with redecorating the building. That May, when Ralph Johnson asked for playground equipment, the League asked the Community Chest for the required $150. In 1950, the center was providing a Y-teen group, Y supervision on the playground after school, a sports program, and films.

By November 1951, however, the McLean Center was being used as a classroom, and was no longer available for recreation. The school board was planning a new addition to the school, and the hut would have to be moved to accommodate construction. In 1953, funds were raised to move the hut to Graham Street, which was done by the spring of 1954. By 1956, however, the recreation program was being run by the Davidson Community Council with help from the county. After almost 20 years, Dave McLean’s vision of a community center had been replaced by other programs.

Nancy Griffith

Nancy Griffith lived in Davidson from 1979 until 1989. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Arkansas and South Carolina history. She is the author of "Ada Jenkins: The Heart of the Matter," a history of the Ada Jenkins school and center.